Jeffrey Snider's latest at Real Clear Markets tackles one of the biggest failures of economics and central banking, the interest rate fallacy:

Low interest rates aren't a central bank providing accommodation, they are instead its worst nightmare being shoved right back in their face.

Snider's argument relies on liquidity preferences:

When comparing possible investment choices, does a bank make an illiquid loan to a questionable borrower, or buy and hold the marketable bond of a potentially even more uncertain issuer? The bond, every time. Liquid, liquid, liquid. And those are just the interest rates we see; what we often miss, and what can never be printed in the paper or on a financial website, is all the possible credit availability that just vanishes, disappears without a trace. While big companies enjoy the privilege of issuing as much debt as they might want, particularly in bonds, and during liquidity-starved times they want to issue as much as possible, what about mid-sized and small companies who don't make it into any interest rate index? The yield on Corporate America's bonds tumble while increasingly any mid-level company gets shut out of the credit market entirely. Liquidity bias also towards the bigger issuers at the expense of everything else; investors will buy every last bond at higher and higher prices offered by Big Inc. while completely avoiding Middle LLC in every credit format.Theinterest rate falls but for all thewrongreasons. Liquidity bias in the marketplace, not monetary policy, is what drives them downward.

This is just a piece of a larger argument by Snider in which the Eurodollar is the actual global reserve currency, offshore and out of the jurisdiction of any particular government or central bank. Moreover, according to Snider, central banks are irrelevant and even harmful in their clumsy attempts to manipulate markets by managing expections. The global financial crisis that launched in 2008 signalled the breaking of the Eurodollar market and there has never been a meaningful recovery since. The second wave of global financial crisis that we're experiencing today actually kicked off late in 2018 with a major liquidity crisis in the Eurodollar market, and we've seen repeated spasms since (e.g. the repo kerfuffle of fall 2019). I read this as the gradual collapse of the USD as global reserve currency, as much by internal contradiction (lack of trust among big players) as by external competition (although that will play an increasing role as the collapes continues).

Here's where MMT provides some useful insight. We know that most of the money in circulation is due to creation by bank lending. The rest, only 5-10%, is due to sovereign government spending in excess of taxation. The Eurodollar system was a massive engine for money creation when it functioned mostly effectively up until 2008. Since then, the lack of growth in money creation has starved the global economy and consequently we've been experienced stagnation as waves of liquidity relief and contraction pass through the system, mainly related to the acceptability of various collateral as a basis for Eurodollar lending. Until COVID, when the whole economy went off the rails, at least temporarily.

So I am looking for a critique of these ideas, which are definitely not part of the mainstream perspective nor even particularly under consideration on the fringes. Does this model capture the true picture of the global economy and its troubles since 2008? What does it tell us about the decline of the USD as global reserve currency? If the Fed really is laughably ineffective, what kinds of policy alternatives actually exist and how should they be implemented?

Regarding policy alternative to the Fed and its toolkit,

note that the US Treasury

has been tapping the credit markets in record levels for months,

while Treasury yields have been dropping steadily despite the enormous volumes.

The issuance has been in significant excess

to the similarly record-breaking levels of stimulus

(I prefer to call it sustenance).

Those Treasuries are the most highly preferred (liquidity again) collateral

for Eurodollar transactions.

That flood of potential collateral may have been exactly the right policy

for moderating acute Eurodollar crises of collateral shortage,

which are actually exacerbated by conventional QE,

which take USTs out of the market.

By chance or by design?

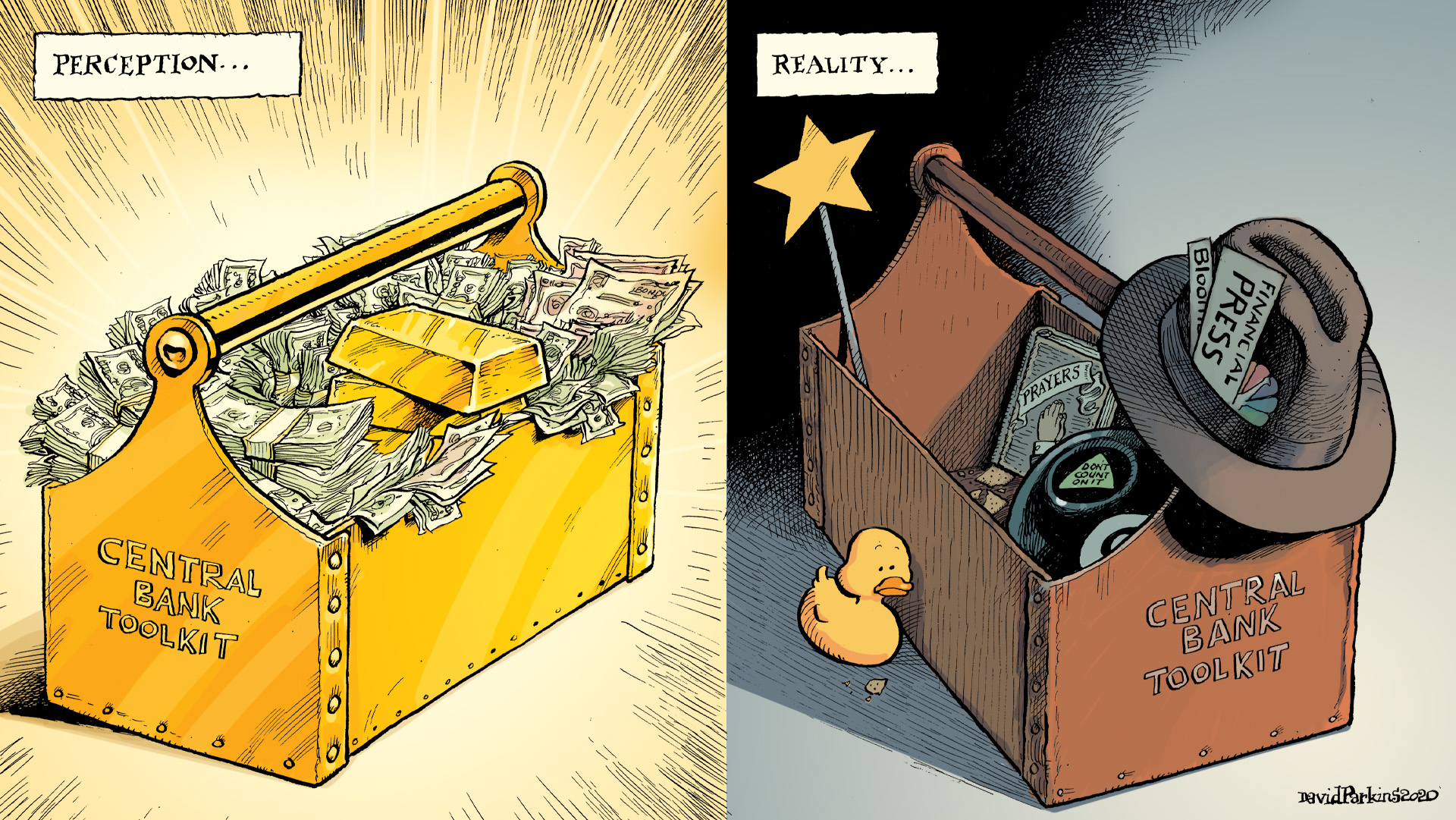

Snider's view on the central bank toolkit, by David Parkins: